Welcome to Iowa, Louisiana

Southern town has Midwestern fingerprints — and Iowa State's — all over it

IOWA, Louisiana — You’re pronouncing it wrong.

“It’s I-uh-way,” Mayor Neal Watkins coached during a visit last February, with nearly invisible inclusion of the O and a drawn-out long A, almost like highway but with a silent H.

A town on Interstate 10 in southwestern Louisiana, about 13 miles east of Lake Charles, has the name, if not the pronunciation, of the Tall Corn State. There are very good reasons for that.

Jabez Bunting Watkins — no known relation to the mayor — was a land speculator. In the 1880s, he offered a discount to Northerners to come south, partially on a railroad that he owned. His sister was married to Alexander Thomson, a professor at Iowa Agricultural College. Watkins persuaded Thomson to come south and he brought IAC president Seaman Knapp with him. Thomson, who Neal Watkins called “the founder” of Calascieu Parish1, is honored with the name of Iowa’s main north-south street2, with Knapp Street a block west. The railroad depot was named Iowa, and Watkins said “we can’t confirm or deny” that’s where the “missing Y” came from, perhaps in the way conductors called out the stop on the train.3

When it became clear that corn and wheat weren’t suitable for the area, Knapp found something that was — rice. The Ames Daily Tribune’s special section for the city’s centennial in 1964 said, “To aid the Louisiana farmers, Knapp chose the best way he knew to teach the farmers how to improve their lot. Instead of simply telling them what to do, he set up demonstration farms showing how his ideas could be used and the results they could produce.” Farms like these became the basis of land-grant universities’ cooperative extension services.

Rice remains a major part of agriculture in the area today. The Tribune also said that in 1902, Knapp “helped prove the South could grow cotton in spite of the boll weevil.”

About 35 miles west of Iowa, the last town on U.S. Highway 90 before the Texas state line is named for one of Knapp’s previous hometowns — Vinton.

‘Kolaches’ and ‘Chicken Runs’

There are plenty of things in the town of Iowa, population about 3,500, that did not come from the settlers of the late 19th century. At Iowa Donuts, the most prominent product is a glorified pig-in-a-blanket labeled as a “kolache.” This culinary blasphemy4 to Americans of Czech descent — and cultural treasure to some Texans — was born around 1953 in West, Texas. The daughter of the meat kolache’s inventor has made clear that it’s more properly called a klobasnek (plural klobasniky). “Yet over time,” Texas Monthly’s “The Texanist” column said in 2022, “the nomenclatural distinction between kolaches and klobasniky has been widely abandoned, which is a never-ending source of rankling among fans of both.”

A much older food-related tradition, which includes costumes, is the Chicken Run, part of Mardi Gras. Children go house to house and, when the residents answer, call out in French the ingredients needed to make gumbo. Then, live chickens are released and the kids try to catch them. Today, the live chickens caught in the run are not the ones that end up in the gumbo, but it’s a great community exercise. “The old-timers love it” when the kids come by, Watkins said.

Watkins enthusiastically shared more about the community’s history. The first oil in southwestern Louisiana was found on the north side of town in 1937. Settler Sylvester Petticrew was discharged from George A. Custer’s 7th Cavalry, two weeks before the Battle of Little Big Horn, on the grounds that he enlisted at the age of 16.

Then Watkins called in his own cavalry: former mayor C.J. Scheufens. “Meet us at the Feed Trough.” The Feed Trough is a former restaurant built by Scheufens out of the remains of a barn wrecked in a hurricane. He furnished it with chairs and other materials that otherwise were going to be thrown away. He built it for his mother, who had lost her lease on a cafe in Lake Charles.

Scheufens also owns the house that was originally the home of Iowa’s first mayor. It sustained heavy damage in a recent hurricane, but he couldn’t remember which one. In that home is a chest brought down by the town’s original settlers.

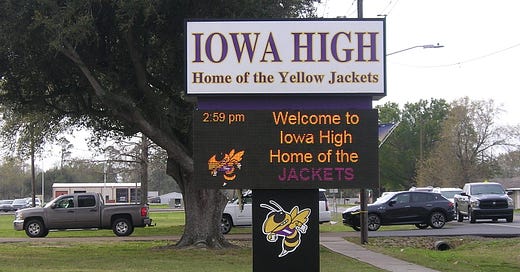

Iowa has an elementary school that used to be the only school, plus a high school on the north side of town. There’s a downtown business block but the chain stores are clustered around the interstate exit.

Some of the city seal’s elements are no longer part of the town. The annual Rabbit Festival moved to Lake Charles, although it still carries the Iowa name, and the outlet mall by I-10 closed.

On the east edge of Iowa, right on the Jefferson Davis Parish line, is Rabideaux Sausage Kitchen. At the front counter it has specialty meats available, from sausages to processed deer to vacuum-packed meat “ready for the pit!” The other half of the store is a sit-down restaurant offering hot food, both in the “ready to eat” and “spicy” senses of the word. One minute you could think you’re at a non-chain gas station or small store somewhere in the state of Iowa, and the next minute you’re looking down at a plate of rice and “boudin balls.” Like many things in Louisiana, it’s hard for a Yankee to explain or digest.

Mardi Gras in Iowa, though, doesn’t involve chasing pigs before eating sausage with our pancakes.

Parishes are Louisiana’s equivalent of counties.

The spelling is inconsistent. The street signs say Thomson, but many addresses along it add a P.

Like one does at the start of “The Music Man”.

Admittedly, it is a tasty culinary blasphemy.

My other work can be found on my website, Iowa Highway Ends, and its blog.

Iowa Writers Collaborative Roundup homepage

Wow! Very interesting to know! Thanks.

Jeff, you not only uncover some great finds, but you write so entertainingly about them. It's a joy. Thanks.