Elections without candidates, ballots without voters

Smushing different votes together creates a lot of paperwork, and there are plenty of blanks to be filled in

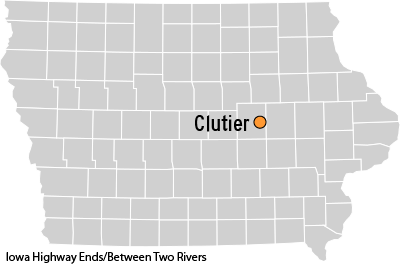

CLUTIER — Many city and school elections in Iowa go uncontested, with only one name on the ballot. The difficult part comes when there aren’t any names at all.

In Clutier, population 213, no one filed to run for mayor or any of the five seats on the city council. It’s not the only community in the state, or even in Tama County, to be in this situation.

“People don’t realize there’s a lot more to being a council member than just attending meetings,” outgoing council member Keith Erickson said. He’s been on the council off and on throughout the years, and at age 82, he decided he had been there long enough.

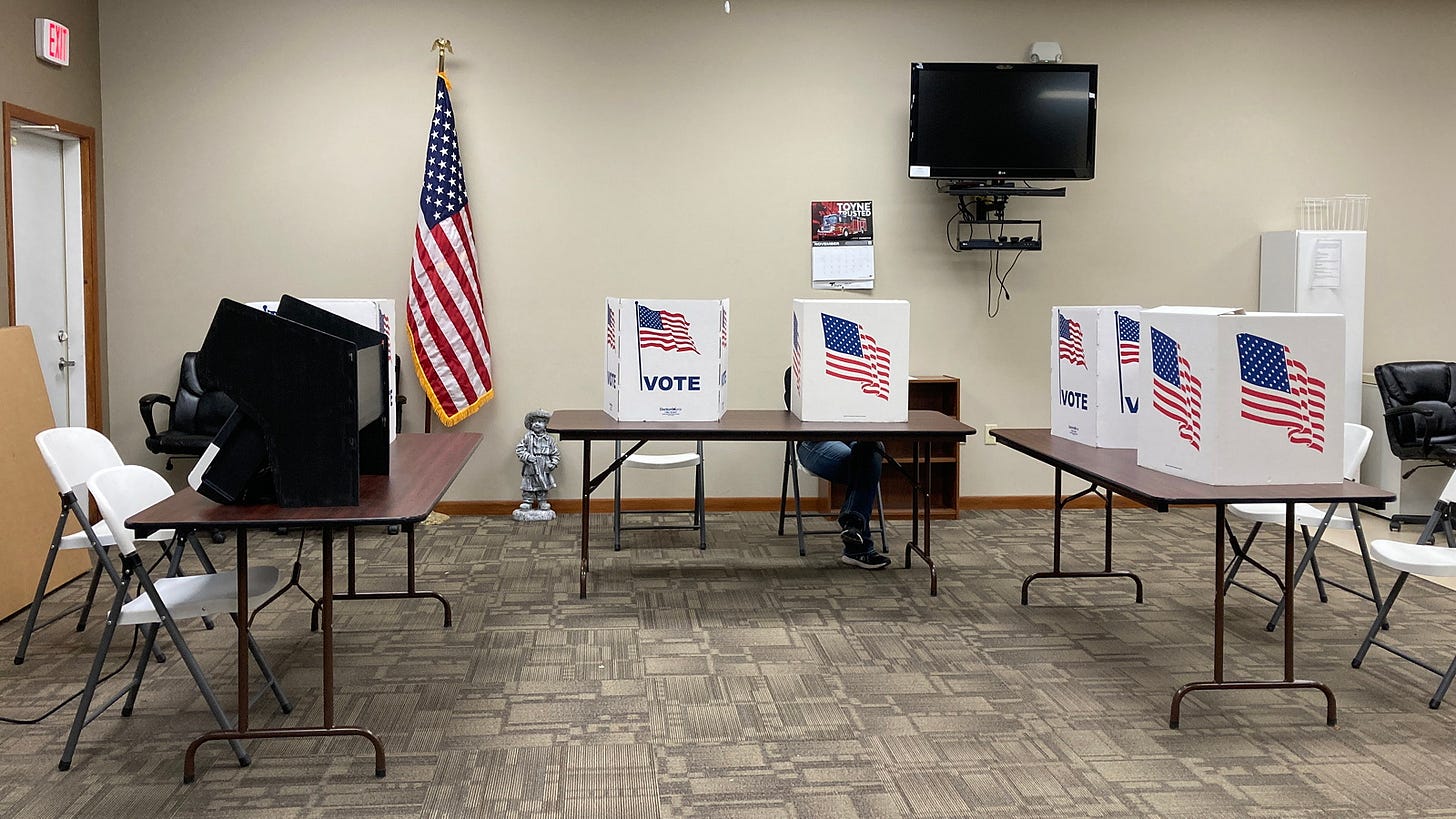

Sharon Knoop had a “cheat sheet” of names for write-ins. She said those people had been brought to her attention as showing an interest in being on the council, and one person had intended to file but didn’t.

Due to the lack of names, unofficial results were not immediately available, but 40 write-in votes were cast for mayor and 159 for city council.

Clutier Public Library board president Barbara Morrison (no relation) brought a banana cream pie to the election workers at the fire station. The 30-voter “rush” between 4:30 and 5:30 accounted for 20% of ballots cast in the Carroll/Oneida Precinct on Election Day. The library held its annual Election Day soup day at the American Legion hall, complete with Czech rohlicky (bread rolls).

On Clutier’s ballot were items that, as recently as 2017, would have taken place on two or three separate election dates: City leadership, North Tama school board seats and a North Tama bond referendum.

Unofficial results indicate North Tama’s proposal to issue $14.85 million in bonds, chiefly to build a replacement for the core 1917 building in Traer, won 65% support Tuesday. An identical proposal, the first part of a long-term plan, fell six votes short of a 60% supermajority in March.

Until this year, the next chance would have come in September, but legislation signed into law in May mandates that all votes on general obligation bonds take place in November.1 From now on, a school district will only be able to put a bond issue before voters twice in a two-year cycle, instead of five times. In even-numbered years, that will mean having to compete for attention with races for president or governor.

This spacing will affect future school votes statewide not just in delayed construction but increased costs. Creston had to drop its push for a second 2023 referendum due to inflation just between March and August. North Tama’s bond request increased by $600,000 from the March number of $14.25 million. (The Clutier area voted against it both times.)

Ballot, ballot, who’s got the ballot?

For decades, no one has filed to run for mayor or city council in Vining, 7½ miles south of Clutier. However, this case may be an act of gamesmanship or even frugality for the village of 54 people. KCRG reported in 2017 that not having candidates officially file meant the tiny community didn’t have to pay to program the voting machines, candidates didn’t have to collect signatures and winners were tallied by write-ins. Another repeat offender on the blank-ballot list is Osterdock in Clayton County, where in 2019 a 4-4 tie on write-in votes meant the mayor was chosen by draw.2

This year for Vining mayor, nine write-in votes were cast at the Elberon Community Center, which served as the York Precinct voting station.

In 2019, school elections were moved from September and combined with city elections into one day in November in odd-numbered years. This means that for regular school board elections, a district can’t have one or a handful of locations for votes specific to it. The intent was to increase voter participation, but it created headaches for county auditors. Auditors not only had to figure out which civic entities would pay for the election and how, but also create more ballots.

School district boundaries have nothing to do with county lines, voting precincts or city limits, and every possibility has to be accounted for. Tama County had 43 permutations of ballots for Tuesday’s elections. That included six styles in York Precinct, where 500 ballots were sent and 56 were used on Election Day, and one style for half a dozen houses in 2¼ sections in the northwest corner of the county that are part of the Grundy Center school district.

But that was not the smallest-population voting area for 2023. Louisa County had to create a ballot pertaining to precisely one house near the intersection of County Road G52 and County Line Road south of Cotter. That house is at the southeast corner of the Highland school district, which happened to be voting on a revenue purpose statement that took up the entire back side of the ballot. Pages 21-22 of the sample ballot packet on the county’s website contained the options for five Highland school board seats (all uncontested) and a yes/no on the revenue purpose statement.

Both the Tama County/Grundy Center school and Louisa County/Highland school ballots had zero votes cast Tuesday.

Among the lesser-known casualties of the 2023 legislation are a school playground levy, a city library levy and the once-renowned Iowa Band Law.

Both Vining and Osterdock were singled out in a 2013 Cedar Rapids Gazette article.

My other work can be found on my website, Iowa Highway Ends, and its blog.

I am proud to be part of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative. If you’re interested in commentary by some of Iowa’s best writers, please follow your choice of Collaborative members: