'Around the World' and across the Missouri

In which a fictional passage frames the final piece of the Transcontinental Railroad

Omaha is connected with Chicago by the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad1, which runs directly east, and passes fifty stations. A train was ready to start when Mr. Fogg and his party reached the station, and they only had time to get into the cars. They had seen nothing of Omaha; but Passepartout confessed to himself that this was not to be regretted, as they were not travelling to see the sights.

— Jules Verne, Around the World in 80 Days

The Transcontinental Railroad was built on the promise of connecting a nation by rail from coast to coast. But on May 10, 1869, the day the Golden Spike was driven at Promontory, Utah, it wasn’t quite there yet.

Four railroads converged on Council Bluffs from the east, one line went west from Omaha, and in between was a little water hazard known as the Missouri River. There was no bridge.

Due to this technicality, the first seamless connection came August 15, 1870 via Kansas City and Denver on a route that hooked up with the Transcontinental Railroad in Cheyenne. Time was of the essence for an Iowa-Nebraska link.

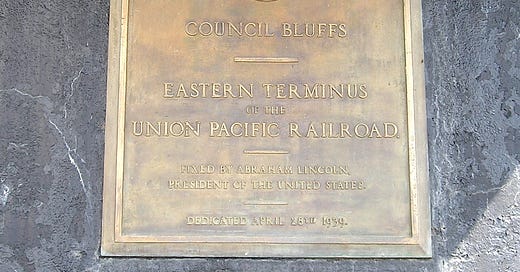

The Pacific Railway Act of 1862 had authorized the Union Pacific Railroad Company “to construct a single line of railroad and telegraph from a point on the western boundary of the State of Iowa, to be fixed by the President of the United States.” Two years later, an executive order from President Abraham Lincoln fixed the start of the railroad, again, “on the western boundary of the State of Iowa.”

The problem was, the Union Pacific and the federal government would disagree on the definition of “on.”

Construction from Omaha began in 1865. Following the completion of the railroad four years later, the contract was wrapped up.2 A separate act of Congress in 1871 authorized the UP to issue bonds for the construction of the bridge. Omaha interests argued that the existence of this act meant the original railroad contract did not include the bridge.

A Chicago Tribune editorial on Feb. 24, 1872, explained the situation this way: If the eastern terminus of the railroad was in Council Bluffs, the UP was obligated to transport passengers and freight across the river. If it was in Omaha, then the UP could demand tolls for the privilege of crossing the bridge. The railroad contracted a “transfer company” to manage traffic across the river, with its owner getting 25% of the profits.

“There is great dissatisfaction expressed, both by passengers and shippers, at this annoyance of transfer, and their language has all that redundancy of profane expletives for which the dialect of the frontier has become famous,” the Tribune said March 28, the day after the bridge’s official opening.

A passage to Iowa

Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days, published in 1872, is set in the last quarter of that year. Verne relays lots of facts in his book as background, but takes literary license with other issues.

Phileas Fogg, who made the bet to travel around the world, and his party catch a train in Omaha at the last minute for an uninterrupted trip to Chicago. In December 1871, this would have been impossible. In December 1872, they would’ve been forced to disembark right after crossing the Missouri River and wait for another train. The Council Bluffs Daily Nonpareil called the transfer a “miserable, tedious, annoying and expensive arrangement.”

The train passed rapidly across the State of Iowa, by Council Bluffs, Des Moines, and Iowa City. During the night it crossed the Mississippi at Davenport, and by Rock Island entered Illinois. The next day, which was the 10th, at four o’clock in the evening, it reached Chicago, already risen from its ruins, and more proudly seated than ever on the borders of its beautiful Lake Michigan.

— Around the World in 80 Days

The spike stops here

In August 1872, the second comptroller of the Treasury Department declared that Council Bluffs was the terminus, because “the word ‘on’ is defined by Webster to signify at, or near.” In spring 1873, U.S. Attorney General George H. Williams3 also sided with Council Bluffs. However, the matter was bound for the courts.

Finally, in March 1876, in Union Pacific Railroad Company v. Hall, the Supreme Court agreed that the right and true end of the railroad was in Iowa.

Holding then, as we do, that the legal terminus of the railroad is fixed by law on the Iowa shore of the river and that the bridge is a part of the railroad, there can be no doubt that the company is under obligation to operate and run the whole road, including the bridge, as one connected and continuous line.

A new bridge was built in 1888, and then those piers were used for the current bridge in 1916. John Weeks has extensive photographic documentation of the bridge.

Council Bluffs got the bragging rights, but Omaha got everything else, from the UP’s headquarters to an Art Deco Union Station built in 1929-31 to the maps and histories about the railroad.

The 1988 book Transportation in Iowa: A Historical Summary noted that the UP had the shortest line in Iowa: 2.08 miles, the distance from the middle of the river to the rail yard. This remained true until 1995, when UP absorbed the Chicago & North Western Railway.

Officially, the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad, although it was the C&RI in 1851-66.

By the end of 1869, the Central Pacific had extended a continuous line southwest from Sacramento to Alameda and San Francisco Bay.

Williams, who had lived in Iowa in 1844-53, resigned in 1875 after accusations of corruption.

My other work can be found on my website, Iowa Highway Ends, and its blog.

I am proud to be part of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative. If you’re interested in commentary by some of Iowa’s best writers, please follow your choice of Collaborative members:

Thanks for this piece! It provides some interesting and entertaining (I like the Jules Verne references and quotes) details that tend to support my own interpretations/prejudices about settlement patterns in the Great Plains.