The high schools are gone, but memories remain

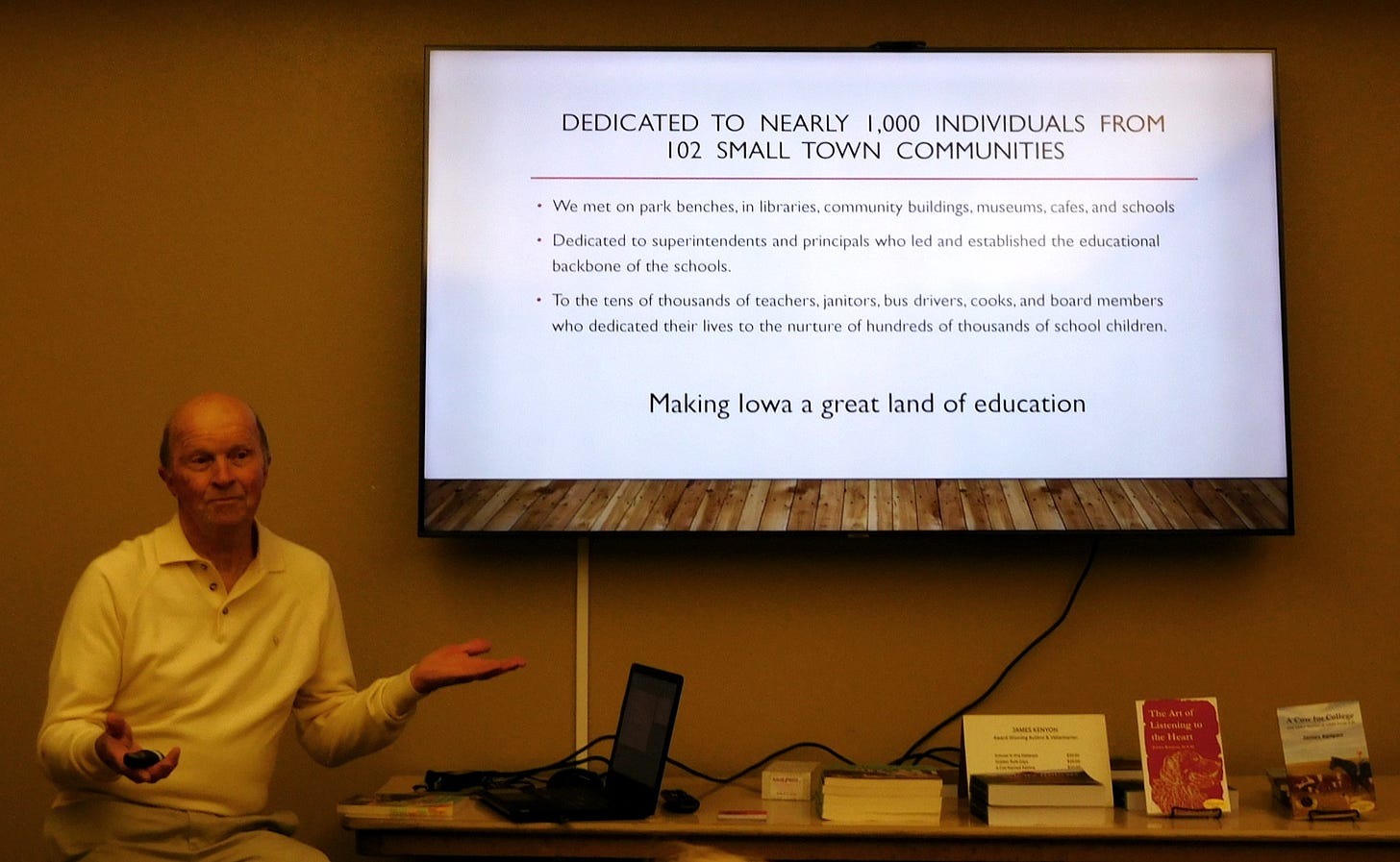

Author James Kenyon shares stories from his book

TRAER — There are countless stories about Iowa’s schools in the 20th century, and James Kenyon spent two years seeking them out. His book, Echoes in the Hallways: History and Recollections of 102 Closed Iowa High Schools, chronicles former students’ reminiscences from influential teachers to school pranks.

Wednesday at the Traer Public Library, about two dozen people turned out to hear him share some of those stories, including from nearby Clutier, Garrison and Beaman. In 2021, Kenyon was interviewed about the book and schools in the Ottumwa and Newton areas.

Kenyon is a Kansas native and retired veterinarian who first compiled a collection about 109 closed schools in Kansas. As a 45-year Iowa resident, it was only natural for him to do the same here. He cold-called libraries across the state to start getting information. He interviewed nearly 1,000 people at cafes, community centers and elsewhere in 2019 and 2020. From that work came a compilation of tales from 102 schools (Adams, Dickinson and Osceola counties each have two).

In his presentation, he shared some of the things about the communities that piqued his interest, from the origin of their names to places that had institutes of higher learning.

In the book, the entry for each town starts with a history lesson about early settlement. Then it covers aspects of some of more than a dozen categories. Stories about pranks and senior trips, days that made lifetimes of memories, are printed for all to enjoy. Notable alumni from each school are mentioned.

Students from long ago talk about teachers or staff members who still stick out in their minds. A Lost Nation graduate remembered a Black music teacher who was a last-minute replacement and taught for two years in the 1960s. “Her social conscience would impact the students for their lifetimes,” Kenyon said as he read from the book.

Graduates who later died during military service get their due. A pair of best friends at Alta Vista lost their lives in opposite theaters of World War II, one at Pearl Harbor, the other at the Battle of the Bulge.

Declamatory clubs, orchestras and other extracurricular activities not offered at today’s smallest schools appeared in many towns in the past. More foreign languages were offered. Thompson, in far northern Iowa, had Norwegian classes, “and if you didn’t like it, you were sent to Latin class.”

Kenyon told a story related to him by Betty (Ferguson) Emrich, Mechanicsville Class of 1944. She and her friends persuaded the superintendent to let them run track. He agreed if the girls did all the same events as the boys. They did, “and the boys’ times improved.”

Kenyon didn’t want the book to be strictly or even mainly about sports, but it’s impossible to talk about the small schools without their highest accomplishments on the field or court. Fierce rivalries are listed, including between towns that eventually became part of the same district, like Beaman and Conrad.

Dorothy (Hadacek) (Haack) Hayek, the last surviving member of Clutier’s 1942 championship girls’ basketball team, said coach John Schoenfelder “made basketball players out of every girl in the school.” When Clutier merged with Traer, residents insisted that the combined school start a girls’ basketball team.

Senior class trips were easier when all the students and a couple of chaperones could pack into a few cars or take a train. In one whirlwind day, Clutier’s 11-student Class of 1941 visited sites in northeast Iowa and southwest Wisconsin.

Many senior classes across the state went to Chicago or Lake of the Ozarks. Beaman’s Class of 1958 switched up their trip from the former to the latter.

Finally, Kenyon goes through the details of each high school’s closure. (Life after that is outside the scope of his project, but is covered in the Iowa Highway Ends timeline.) He counts up the most common last names of graduates and lists the last student in alphabetical order from the final year.

Kenyon had a special challenge for that part of the presentation Wednesday as he read Clutier’s very Czech roster. Every teacher who’s new to an area would benefit from getting a pronunciation guide.

All but a few buildings featured in the book have closed entirely, including Everly, the most recent, in 2019. (Clay Central-Everly’s K-6 students remain in Royal, and even had a homecoming parade this fall.) Albion’s building, used for decades as a community center, was torn down less than a year before Kenyon started work on his book.

Kenyon’s other books are a memoir about Kansas farm life in the 1950s, reflections on his career as a veterinarian, and a collection of stories about cats and the people who loved them.

My other work can be found on my website, Iowa Highway Ends, and its blog.

I am proud to be part of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative. If you’re interested in commentary by some of Iowa’s best writers, please follow your choice of Collaborative members:

School closures are such an interesting and emotionally-charged topic and it's still occurring today. Our oldest finished his elementary days at Arthur Elementary and our youngest is completing his final year at Madison Elementary. CRCSD has a tradition of the senior walk in which seniors return to their elementary schools to take one final pass through the halls in their caps and gowns while the current elementary students cheer them on.

I first learned about this when I was working at Hoover Elementary. Teachers gave me a heads up that students wouldn't be available during on this day at this time because there would be this special event. I thought, "What? This is a tradition? I went to Taylor and then Jefferson--why don't I already know about this?!" Here's why. I was a nomad. I didn't get to embrace this tradition because my home wasn't stable enough to allow me to stay in one area for 14 years. During those years, my parents divorced each other, and then divorced the people that they had remarried. A family member had passed away which necessitated another move from our trailer to the inherited home. I also attended school in Mount Vernon and actually ended up graduating from a high school in Bellevue, NE when I was court-directed to go live with my dad because the home that I shared with my mom was no longer deemed safe because of an abusive step-dad.

Here's the thing. I'm not the exception. I attended Hoover's senior walk that day instead of working with my usual students. There were only a few seniors that attended. Where were all of the seniors? I suspected most had a past like mine and that a very small percentages of students had the luxury of staying in the same area for 14 years. I suspect many of those seniors during their 14 years needed to relocate due to employment, housing availability, divorce, and many more reasons.

Our oldest reflected that when it was his turn to do his senior walk, there would be no students in Arthur to cheer him on. They would all be across the street at Trailside Elementary. I told him that was okay. Kids at Trailside Elementary would hopefully have more collaborative learning spaces, accessibility for students in wheelchairs, and comfort so they could learn with an updated HVAC system that can keep up with climate change and keep them safe from radon. Hopefully, their speech teacher has their own space so it's easy for their students to focus on the lesson instead of feeling claustrophobic in a closet or disrupted by a student having a meltdown at the end of the hall. I reminded him that it is more important to provide teachers and students with the best possible spaces to learn in for the years, maybe even months, that they are with us than holding on to a tradition with a death grip that happens once during your senior year and lasts for about 10 minutes.