Paid subscribers will find a Zoom link at the bottom of this column. The last Friday of every month at noon is the Iowa Writers' Collaborative Office Lounge. It's an opportunity to interact with members of the Iowa Writers' Collaborative. If you are a paid subscriber to any member of the Collaborative, you will find the link below. If you aren't a paid subscriber, please consider becoming one.

There are two places in southwest Iowa that play special parts in the development of the state’s present-day boundaries. This is a look into those places.

An in-depth examination about the attempts to set the northern and western borders in the 1840s is on Iowa Highway Ends.

wrote recently about how those proposals would have affected the Iowa Great Lakes.East Omaha?

Although Abbott Drive and Locust Street intersect, the Iowa highways on those streets in Carter Lake never met — because their intersection is in Nebraska.

Coming south from Eppley Airfield, a few hundred feet after turning onto Locust Street, there was a big marker proudly proclaiming “Welcome to Carter Lake, Iowa.” However, unlike an earlier version, the outline of the city and lake itself were turned sideways. After a Casey’s was built in 2016, this marker disappeared. Locust Street was Iowa Highway 347 from 1937 to 1986.

Abbott Drive has “Welcome to Iowa” signs on either end of Iowa Highway 165, the shortest signed state highway. Well, usually it’s signed. There are only two shields, and they vanish on occasion. According to Google Street View, one that was there in November 2022 was gone in May 2023.

The border along the Missouri River, including the DeSoto Bend and Carter Lake areas, was delineated in the 1892 U.S. Supreme Court case Nebraska v. Iowa. Omaha’s mayor made one more push to seize Carter Lake for the Cornhuskers in 1935. Because the river kept shifting, the border was defined again in the 1972 case Nebraska v. Iowa.

Upriver from Carter Lake and west of Sloan, land included in a reservation of the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska in 1865 had shifted to the Iowa side by 1943 and was seized by the federal government in 1970. The tribe has fought to get it back ever since. In November 2023, the U.S. House approved the Winnebago Land Transfer Act of 2023, and on May 1, the U.S. Senate Indian Affairs Committee advanced it. That land will not change states, but it will become part of the reservation.

Drawing the line for the Honey War

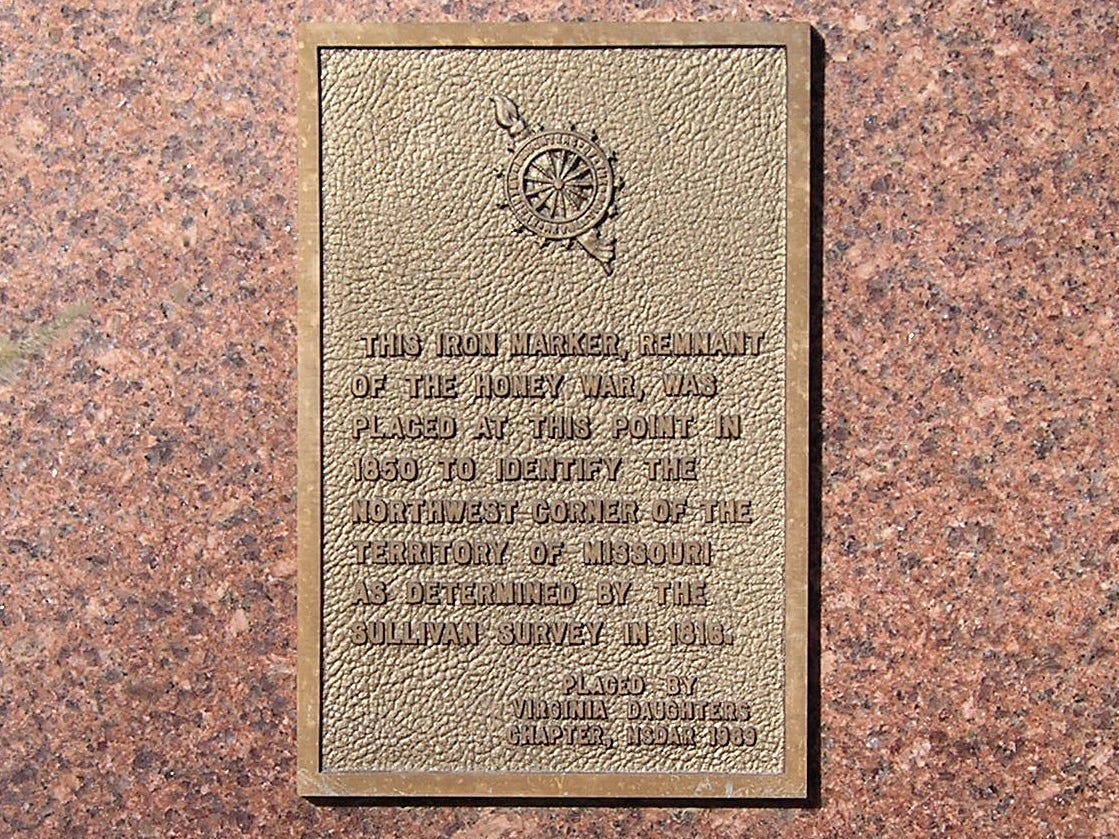

It is not easy to get to the Sullivan Line marker southeast of Bedford. I could hear scraping on the bottom of the car as I followed what was pretty much a cowpath east of County Road N56. Don’t try to go there when the roads are muddy.

The marker is directly north of the straight part of the Missouri-Kansas border. The northwestern part of Missouri, including St. Joseph, was not part of Missouri when it became a state in 1820. The Platte Purchase was not attached to it until 1837. Members of the Potawatomi tribe who had moved there from the Great Lakes were evicted to Council Bluffs.

When surveyor J.C. Sullivan was told to survey the northern border of Missouri Territory in 1816, he started where the marker is today. From there he was to go east to the “rapids of the river Des Moines.” Sullivan not only didn’t draw a straight line, he looked for the wrong rapids. A second attempt at setting the border went 10 miles farther north, creating confusion over jurisdiction.

The Honey War arose from an attempt to collect taxes on “bee trees” owned by Iowans living in the disputed area. The sheriff of Clark County, Missouri, and his posse were arrested by the Van Buren County Sheriff and his posse, and sent first to Burlington, then Muscatine. Missouri’s governor ordered out the state militia.

The National Park Service writes about this colorful chapter in Iowa history:

Iowa created its first territorial militia and mobilized troops of its own, with self-provisioned and outdated weapons, including rusty swords left over from the War of 1812, Revolutionary War muskets, and farming implements refashioned into weaponry, such as a butter churn dasher and a plow blade on a chain. The governor of Iowa supplied 5 barrels of whiskey to his hastily improvised army, and at their camp soldiers became eager to vengeance, shouting the battle cry, “Death to the invading pukes!”

The Iowa National Guard continues today, but the governor does not supply whiskey.

After another survey by federal engineer Albert Lea, and reliance on notes by Zebulon Pike, the 1849 Supreme Court case Missouri v. Iowa settled the dispute in Iowa’s favor. The border was ordered to be marked. Nearly 50 years later, no one could find the markers and the Supreme Court ordered it to be marked again.

The Honey War involved two sides firing nothing but insults at each other and resulted in no casualties — in other words, the perfect conflict. Unfortunately, since college football had not been invented yet, and then for other, sadder reasons, the black-and-gold team from Iowa and the black-and-gold team from Missouri would not strike up a lasting rivalry. The perfect trophy is there for the taking — a carving of a “bee tree.”