When does 1 + 8 = 1?

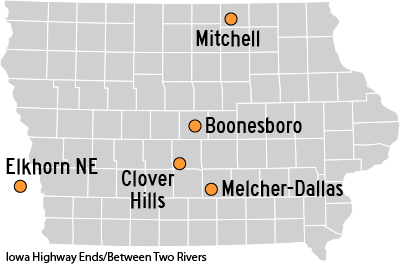

On March 24, 2005, the 18th-largest city in Nebraska ceased to exist.

Under Nebraska law, a city with a population above 400,000 is a “city of the metropolitan class,” and there is only one that fits the bill — Omaha. This class of city gets a plethora of powers no other city has, including the ability to annex any city with a population below 10,000 without that city’s consent. The suburb of Elkhorn, west of Omaha, was rapidly growing and conceivably could have limited Omaha’s growth. Just between 2000 and 2004, Elkhorn added more than 1,500 people.

Omaha planned a strategic annexation of land to create a connection to Elkhorn and swallow it. Elkhorn tried to counter with annexations that would get it past the 10,000 mark. In a court case that included issues about timing of public meetings, the Nebraska Supreme Court ruled in 2007 that Elkhorn’s annexation was six days too late.

More than a century earlier, Des Moines had done something very similar.

In 1890, Des Moines’ city limits were 28th Street, University Avenue, East 22nd Street and Hartford Avenue. Eight towns surrounded the city on three and a half sides.

State Sen. Col. Conduce H. Gatch introduced legislation in 1890 to expand Des Moines’ city limits by 2.5 miles in every direction. Technically, the law applied to any city with a population over 30,000 in the 1885 state census, but Des Moines was the only one that qualified. The expansion created a box bounded by 63rd Street, Aurora Avenue, East 43rd Street and Watrous Avenue. It also consumed (clockwise from the west side) Greenwood Park, University Place, North Des Moines, Capitol Park, Easton Place, Grant Park, Chesterfield and Sevastopol.

Other large Iowa cities have annexed bordering communities, but the 1890 expansion of Des Moines stands out for both its scope and legislative action.

Bye bye, Boonesboro

The Boone County Courthouse is distinctively not in downtown Boone. It’s located in what used to be a separate community, Boonesboro, which was named the county seat in 1851.

An 1875 map of Boone County clearly separates Boone, on the main Chicago & North Western railroad line, from Boonesboro, on a spur line to coal mines. This was a problem. Quoting from the 1914 History of Boone County, Vol. 1:

The citizens of Boonesboro failed to comply with the requirements of the railroad company, and the result was that the road ran down Honey Creek to the Des Moines River, thus leaving Boonesboro out in the cold. This caused great excitement in Boonesboro, and the friends of the town throughout the county listened to their wails with feelings of sympathy. Although the first courthouse had only been built eight years, the people of Boonesboro at this early date wanted a new courthouse built on the public square. The railroad company had laid out the Town of Boone, a mile and a half east of Boonesboro, and the people of the latter town became very uneasy lest the new town should in some way secure the removal of the county seat.

A courthouse was built in 1865, and residents thought this meant Boonesboro’s future was secure, “regardless of any rival town which the railroad might build up.” They were wrong.

On March 21, 1887, Boone annexed Boonesboro and seized county seat status. When it came time to build a new courthouse, the Boonesboro neighborhood successfully stopped the county from buying a new site. The present courthouse was built in 1916 and opened in 1917.

Chewing up Clover Hills

West Des Moines’ early growth came at the expense of one incorporated place.

Clover Hills was in the area around 12th Street and Grand Avenue. In 1948, residents of the Penrod Place subdivision sued to be severed from Clover Hills and be annexed by West Des Moines because the former was not providing adequate municipal services. Two years later, the town voted to dissolve, and West Des Moines annexed it.

“The specific case of Clover Hills may never be of historic importance to West Des Moines, but will be added evidence that West Des Moines no longer can be considered the swaggering little ‘railroad town’ it was at birth,” Des Moines Register columnist Walt Shotwell wrote April 2, 1950.

A decade later, West Des Moines annexed nearly all of Walnut Township, from University Avenue south to the Raccoon River and west to the county line. The village of Commerce, near the Raccoon, was part of it. Interestingly, the Secretary of State’s Office list of cities includes a line for Commerce with a note that it’s defunct, but the Des Moines Tribune in 1961 said it had never been incorporated, which allowed West Des Moines to add it.

Come together, right now

In November 1954, the towns of West Mitchell and Mitchell merged. Due to the way Iowa Code was structured at the time, West Mitchell officially annexed Mitchell and then renamed itself Mitchell. In 1967, the law was changed so that consolidation was achieved not by one community annexing another, but rather as a merger of equals. A Drake Law Review article from 1969 mentions the law in the larger context of municipality creation and border changes under Iowa Code.

In Marion County, Melcher and Dallas had gone hammer and tongs at each other for decades. In 1976, covering the adjacent cities’ rivalry, the Des Moines Tribune said Dallas contended Melcher owed a $36,875.91 water bill. A decade later, the long argument between neighbors turned into a marriage. Melcher-Dallas, established in 1986, is the only city consolidation since the law changed in 1967.

Unlike Elkhorn, a tiny town in Iowa bordering a big city has a say in its continued existence. There will be no swallowing suburbs here, and opposition in Iowa to consolidation of any sort remains strong.

Huxley recently expanded its city limits so far east that it touches a western extension of Cambridge. Welcome to Huxbridge?

My other work can be found on my website, Iowa Highway Ends, and its blog.

I am proud to be part of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative. If you’re interested in commentary by some of Iowa’s best writers, please follow your choice of Collaborative members: